You already know Superman. He’s the first comic book superhero, the guy who set the stage for everyone who followed, from Batman to Wolverine to Mighty Mouse.

However, you might have a very limited view of Superman. You might think of him as a big blue boy scout, an eternal do-gooder whose unimpeachable morals and invulnerable strength make him a bit dull.

But he’s so much more, a complex character who captures the entire moral appeal of power fantasies. You only need to look at the many great comics that have come to define the superhero over the years. After reading these comics, you’ll not only understand why people like Superman—you’ll understand why an entire genre manifested in his blue and red wake.

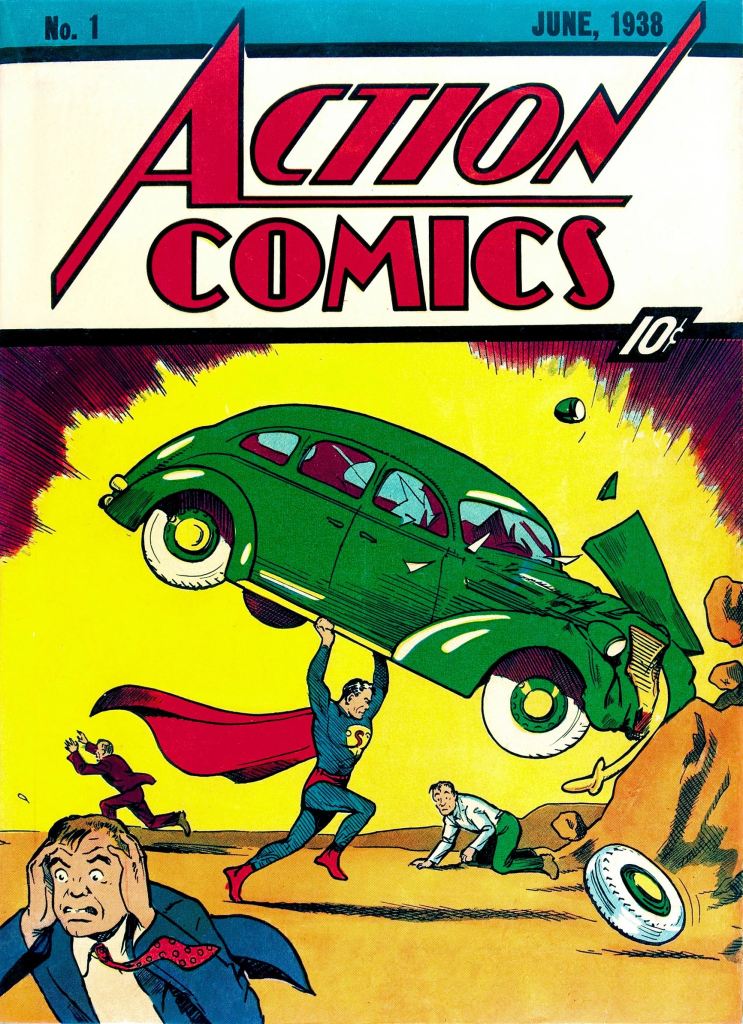

Action Comics #1 (1938)

It is shocking to see how fully formed Superman arrived in his 1938 debut. No, he still lacked many of the qualities that would later be added by the first radio and television shows—Kryptonite, Lex Luthor, even the ability to fly. But the core of Superman was there from the beginning, on display in Action Comics #1.

Written by Jerry Siegel and illustrated by Joe Shuster, the first story in Action #1 begins with an origin tale that became the stuff of American myth, a “hastily-devised space ship” heading to Earth from a destroyed planet. The baby, of course, grows up to be Superman, with the ability to “leap 1/8th of a mile in a single hurdle” and “run faster than an express train.”

However, the stories in Action aren’t really about the cool things that Superman can do. Rather, they’re about his ability to save an innocent man condemned to death and spooking a wife beater. Even better are the scenes in which Superman takes his mild-mannered Clark Kent persona, quietly cheering on Lois Lane for stepping up to a pushy cad.

Action #1 set the groundwork for Superman and the entire superhero genre by establishing the hero as the Champion of the Oppressed.

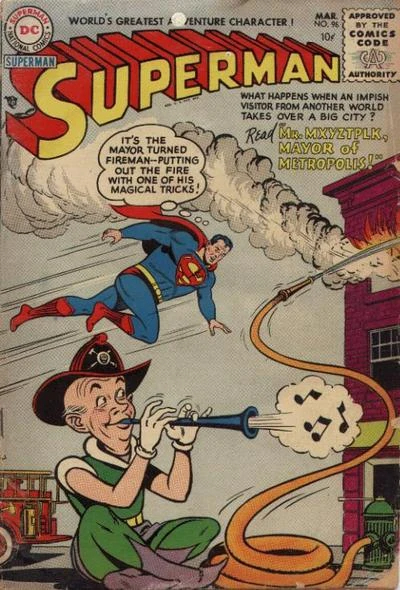

Superman #96 (1955)

Superman became impossibly strong in the Silver Age, when writers began telling high sci-fi and even fantasy stories with Superman at the center. As much as modern readers sometimes dismiss the stories as goofy or tone deaf, they also presented unique ways of challenging the all-powerful hero.

Superman #96 is a perfect example of this tendency, and not just because the issue features the reality-bending imp Mister Mxyzptlk. The issue begins with the story “The Girl Who Didn’t Believe in Superman” by Batman scribe Bill Finger and penciler Wayne Boring. The tale has almost laughably low stakes, as Superman meets a little blind girl who refuses to believe that Superman is anything other than a fairy tale told by her mother.

Many Silver Age comic book stories amounted to little more than superheroes playing pranks on people, especially Superman stories. “The Girl Who Didn’t Believe in Superman” has the same structure as those prank plots, but there’s an inherent sweetness to it. Superman seeks less to prove his existence and more to show the young girl the beauty of the world, something that she believes was robbed from her when a car accident stole her sight.

While there’s more than a little ableism to the resolution in which Superman cures the girl’s blindness, the resolution also captures the entire point of superheroes: to fantasize about power making the world a better place.

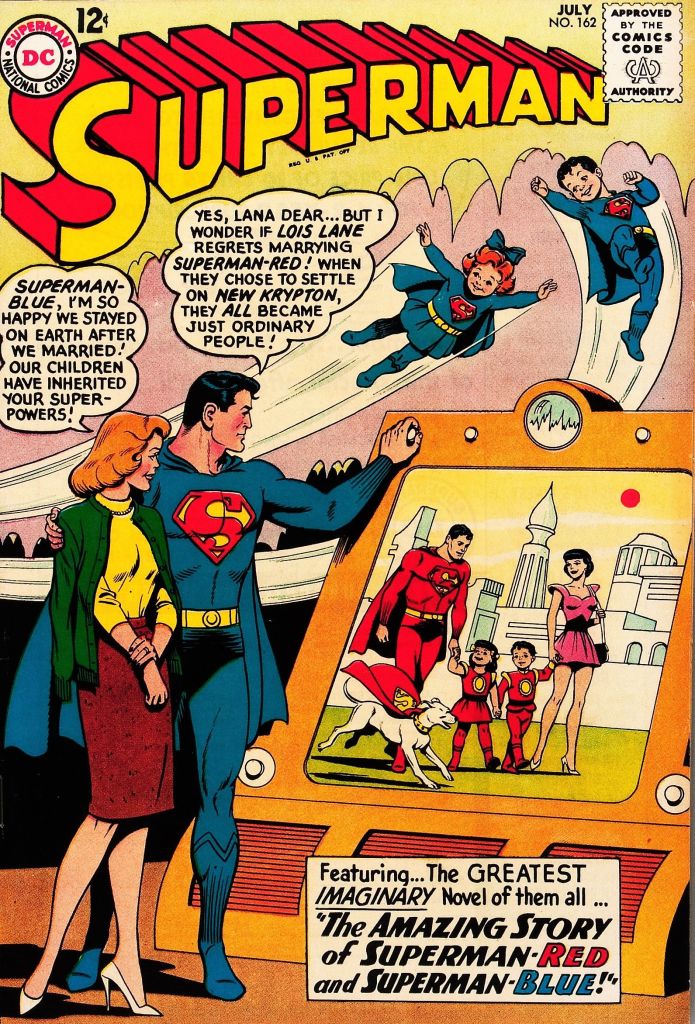

Superman #162 (1963)

Having survived the superhero implosion that followed World War II, Superman and DC Comics enjoyed a renaissance in the Silver Age with the science fiction takes on heroes such as Green Lantern and the Flash. And yet, no sooner did Superman restore his place atop the superhero mountain than a new challenger arrived in the form of Marvel Comics and its conflicted characters.

Although the Marvel Age of Comics had just begun when “The Amazing Story of Superman-Red and Superman-Blue” appeared in Superman #162 in 1963, it’s clear that writer Leo Dorfman, working with pencilers Curt Swan and Kurt Schaffenberger, was responding to the marvelous competition. The story begins on a note more familiar to Peter Parker or Ben Grimm than to Clark Kent, with the mild-mannered reporter being passed up for a raise and Superman castigated by inhabitants of the Bottle City of Kandor for all the promises he’s failed to keep.

As a solution, Superman splits himself into two distinct clones, dubbed Superman-Red and Superman-Blue. Superman-Red and Superman-Blue (with some help from Supergirl) solve all the world’s problems, while also returning the people of the bottle city of Kandor to normal size and, uh…, hypnotizing all the world’s criminals (including Fidel Castro, because ’60s!) into becoming moral. They even find a way to restore Lex Luthor’s hair, thus erasing his evil (again, ’60s!). By the end of the story, Supergirl has found her place with the Legion of Super-Heroes, Lana Lang gets to marry Superman-Blue, and Lois Lane gets her man with Superman-Red.

And they all live happily ever after. No, seriously, that’s the end. Yet, before any Marvel Zombie dismisses “The Amazing Story of Superman-Red and Superman-Blue” as just another example of DC’s saccharine storytelling, we’re reminded that this is an imaginary story, not something that Superman actually does in canon. In other words, this issue gets at something much bigger at the core of the character: for all of his power, Superman cannot have the happy life he most wants, a sacrifice he’s willing to make in order to do the most possible good.

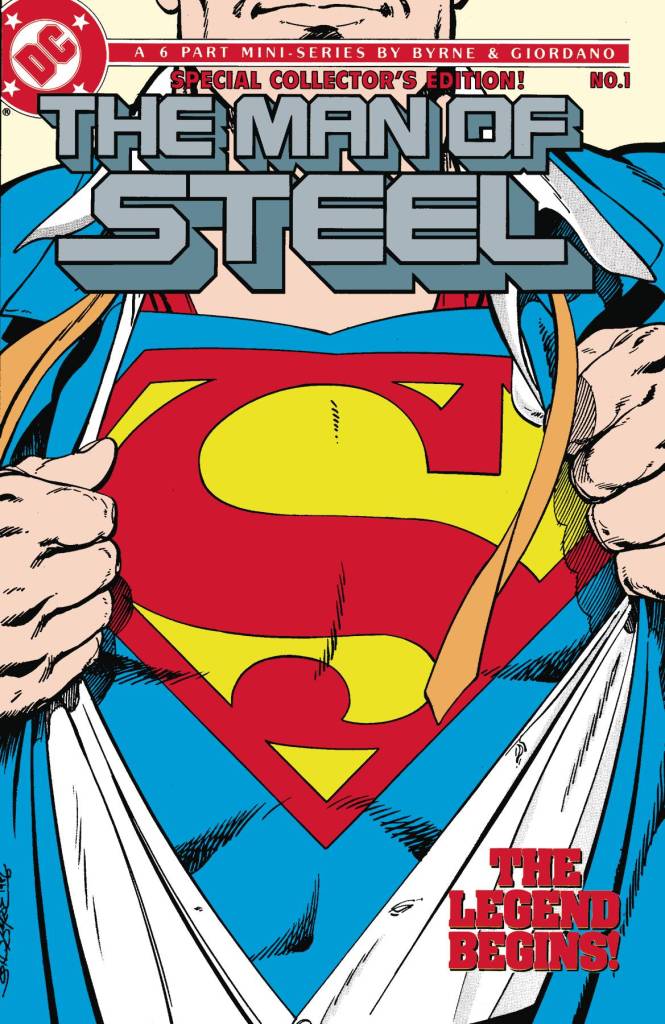

The Man of Steel (1986)

On one hand, The Man of Steel reboot by John Byrne was devised as an explicit rejoinder to Silver Age excess. Like Crisis on Infinite Earths and Batman: Year One, The Man of Steel sought to redefine Superman and his mythos for a modern ethos, which included some unequivocally great decisions, such as reimagining Lex Luthor as a respected businessman instead of a glowering supervillain, but also stripped away Superman’s abilities. Gone were super-ventriloquism and super-kissing. Unlike the live-action Man of Steel who flew backwards around the planet to turn back time and save Lois Lane in Superman (1978) less than a decade earlier, this Superman was bound by greater rules of reality.

Yet, unlike almost every other creator who would try to make Superman gritty and relatable, Byrne understood the fundamental sense of wonder inherent to the hero. As demonstrated in the series’ first issue, which begins in the scientific wonderland of Krypton and then cuts to a Smallville High football game in Kansas, Superman isn’t Superman without the fantastic.

By placing Superman in a more realistic world, Byrne makes familiar moments all the more magical. There’s genuine awe in the panel of Clark flying for the first time in issue #1, the sight of bullets bouncing off of Superman for the first time in issue #2 feels amazing once again. Byrne doesn’t do away with these fantastic feats. He just grounds them in a world in which Lois Lane doesn’t fall so quickly for Clark Kent and in which Lex Luthor dismisses the idea that Clark and Superman are the same guy because he can’t believe anyone so powerful would pretend to be weak.

The Man of Steel didn’t make Superman relatable by taking away his powers. It made him relatable by heightening the emotions related to those powers.

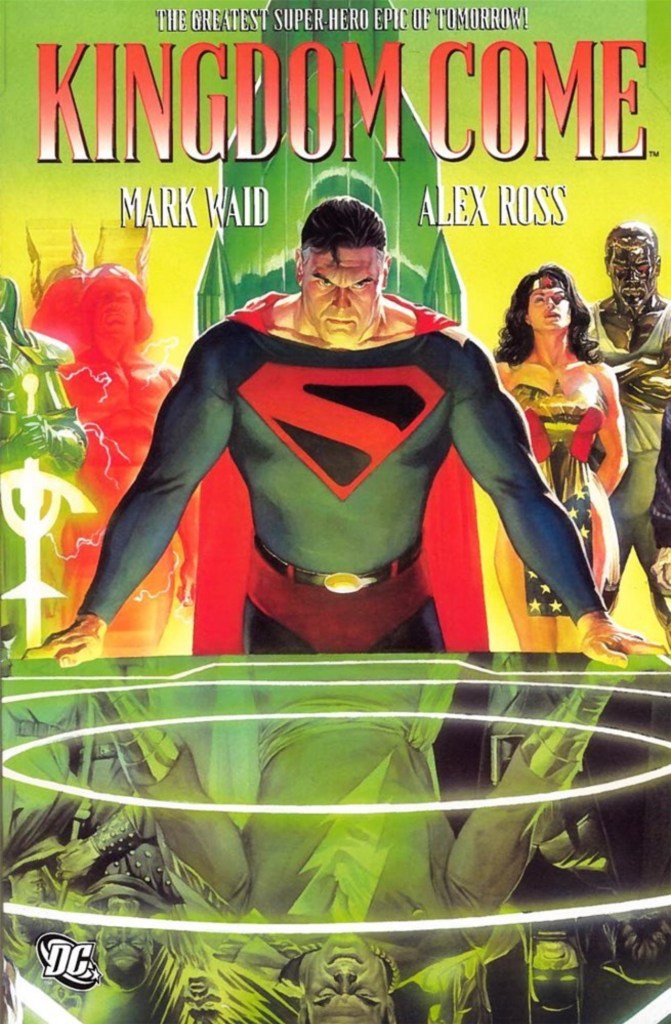

Kingdom Come (1996)

Kingdom Come released in 1996, right in between the Image revolution that saw Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, and other Marvel standouts launch their own flashy creator-owned ongoing series and the dawn of the Authority and the Ultimates. Outliers such as Wolverine and the Punisher had become the norm, as edgy anti-heroes took the stage, bringing with them a moral flexibility even the Golden Age Superman and Batman would find objectionable.

As such, Kingdom Come functions just as much as a statement on the comics industry as it does a standalone story. Painted by Alex Ross and written by Mark Waid, Kingdom Come takes place in the DC Universe’s future, where edgy ’90s super-people spend all their time in meaningless brawls among one another, paying no attention to the regular people they harm along the way. Worse, all of the classic heroes have ceded ground to the next generation, including Superman, who has retired to a Kansas farm after Lois Lane’s death.

Although Kingdom Come isn’t strictly a Superman story, it does put Supes back in the center of the DCU, where he belongs. When his patience with the next generation reaches its end, Clark dons his corny old trunks and cape and teaches the kids a lesson in the most Superman way possible: by inspiring them to be better. Waid wraps the inspirational tale around a delightful superhero mash, complete with fun cliffhangers and reveals, all brought to life by Ross’s hyper-realist art.

Superman For All Seasons (1998)

Superman For All Seasons comes from the legendary team of Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale, creators of Batman: The Long Halloween and Spider-Man: Blue. But where those properties told moody stories about the inner turmoil of big-name heroes, For All Seasons offers a hefty dose of Americana.

As they do in those aforementioned series, Loeb and Sale take Superman back to fundamentals. That means exploring the central contradiction of Superman, an all-powerful alien raised as a wholesome midwesterner. For All Seasons follows Superman’s last months in Smallville and first months in Metropolis, where he carries the lessons he learned into the rest of the world.

Sale heightens his exaggerated, cartoony style to make both Clark and Superman big lunks, retaining that central charm even when he’s flying through the Metropolis sky. Sales’ fluid line work keeps the compositions loose, helping us see all the people in his depictions of overcrowded Metropolis and lush Smallville. Even better, Bjarne Hansen adds warm watercolors to the images, giving the book the feel of a Norman Rockwell painting with superheroes in it.

As always, Loeb knows how to distill a classic character’s essence into a single scene and line. For All Seasons offers many contenders, including a wonderful sequence of Clark saving people during a tornado storm in Smallville. But the best might be the first splash page with him as Superman, responding to a little boy who compliments his suit. “Thanks,” smiles the godlike galloot. “My Mom made it for me.” That one page is enough to explain everything great about Superman. And then Loeb, Sale, and Hansen give us 100 more.

What’s So Funny About Truth, Justice, and the American Way (2001)

In another world, “What’s So Funny About Truth, Justice, and the American Way,” the lead story in Action Comics #775, would read as a solid, but somewhat redundant story about why Superman matters. Written by Joe Kelly and penciled by Doug Mahnke and Lee Bermejo, the issue pits Superman against the Elite, a crass team of anti-heroes moddled directly on the Authority. Led by the English telepath Manchester Black, the Elite considers Superman too out of date, too stodgy for the modern world. By the end of the story, Superman has proven them wrong.

Again, it’s a good story, but it covers a lot of the same ground as Kingdom Come, then only five years old. But Action #775 hit shelves a few months before 9/11. America was about to need a Superman more than ever, less for the power fantasy he offered than for the moral guidance he provided.

For Black and the Elite, Superman doesn’t use his powers correctly. He’s incredibly strong and fast, but he doesn’t use those to beat up bad guys or stop evildoers preemptively. To prove their point, they put Superman through a type of gauntlet, one that leaves Supes battered and exhausted, but ultimately victorious.

At the climax of the story, we see a blood-soaked and haggard Superman towering over Black, looking furious. And it seems like “What’s So Funny…” is going to give us exactly what we thought we wanted, a show of power in pure and righteous vengeance.

But Superman doesn’t beat Black to a pulp. Instead, he gives a speech that confirms that Superman is out of step with the times and that’s a good thing, because the times are very, very bad, and we need inspiration now more than ever, even more than five years prior.

Superman: Red Son (2003)

Anyone who sees writer Mark Millar‘s name on the cover and then reads the synopsis to Superman: Red Son thinks they know what they’re getting. An Elseworlds tale set in an alternate reality, Red Son imagines what would happen if Kal-El’s rocket landed not in Kansas, but on a state farm in Lenin’s Russia at the height of the Cold War.

But don’t get fooled by Millar’s usual M.O. or the image of Superman with a hammer and sickle in place of his familiar “S” shield, drawn by artist David Johnson. Superman: Red Son understands the fundamentals of the character, and only reinforces them by taking him far from his element.

Nothing demonstrates this fact better than a scene early in the book, when Lois Luthor (née Lane) gets her first in-person look at the hero. Having retired after marrying (non-criminal) genius Lex Luthor, Lois gets pulled back into the journalism game by Perry White when Lenin introduces his Superman to the world. While the rest of the country prepares to counter what they consider a new threat, including the creation of a new air force corps under the leadership of former Soviet POW Hal Jordan, Lois sees the Man of Steel himself fly into Metropolis.

Everyone else recoils in fear, but Lois recognizes Superman’s true goal in invading American space. The globe atop the Daily Planet has come loose, barreling down onto the people below. A mother cradles her child as the globe nears them, and the boy lets go of his balloon.

In a wonderful, iconic splash page, we see this Superman, who doesn’t speak English and represents the West’s greatest enemy, holding the globe aloft in one hand and daintily handing back the child’s balloon in the other, smiling at the people he just saved.

For all of its charged political content and alternate reality shenanigans, that’s what Red Son is about, reminding us that Superman is always Superman, no matter where his rocket stops.

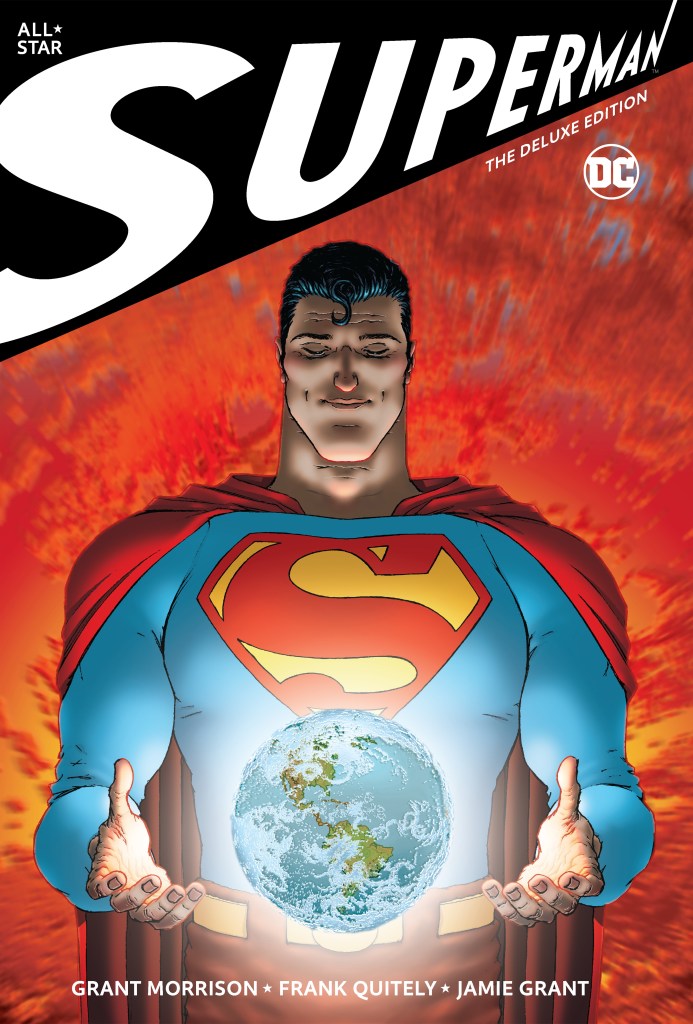

All-Star Superman (2005-2008)

As if in direct defiance to anyone who takes the wrong lessons from The Man of Steel, All-Star Superman begins with Superman getting even more powers. When Lex Luthor detonates a massive bomb in space, he manages to imbue his enemy with greater abilities. But those abilities soon begin to deteriorate Superman’s body, forcing him to face his own death.

Writer Grant Morrison and artist Frank Quitely borrow from the structure of the trials of Hercules for All-Star Superman, the 12-part series that finds the hero completing his final tasks before his death. But the series operates more like a new gospel for the super-heroic age, an ambition suggested by the Renaissance-style images of Superman ascending after leaving a message for his followers.

Pretentious as that might sound, All-Star Superman features Morrison’s Silver Age love at its best. They embrace outrageous elements of the Superman mythos, including a trip to the Bizarro world and a face off against mythic figures Hercules and Samson. Yet, within those tall tales, Morrison and Quitely find moments of real pathos. It’s not just the oft-shared scene in which Superman pauses to comfort a suicidal girl. It’s the tender kiss that he and Lois share after she gets superpowers, it’s the realization that he cannot prevent his father’s death, it’s Lex Luthor’s realization that all we have is one another.

All-Star Superman best represents the potential of Superman stories as a moral good, fantasies that help us make sense of a world that feels like evil always wins.

Superman Smashes the Klan (2019-2020)

Written by Gene Luen Yang and illustrated by the Japanese duo known as Gurihiru, Superman Smashes the Klan has its roots in an incredible real-world story. In 1946, authorities used the story arc “Clan of the Fiery Cross” from the Adventures of Superman radio show to reveal secret information about the Ku Klux Klan, leading to a decrease in the terrorist group’s membership.

Superman Smashes the Klan revisits the storyline from a personal perspective, emphasizing Superman’s role as an immigrant in America. As the Man of Steel comes to the aid of the Lees, a Chinese-American family who becomes the target of hate when they move to Metropolis, Clark wrestles with his own feelings of isolation from the world that has adopted him.

Yang fills the story with real pathos, showing a side of Superman rarely explored in comics and reminding readers about the pervasive nature of xenophobia. He does so by building on established Superman lore, including the increase in Superman’s powers in the 1940s, and by introducing an appropriately named new side character in kid reporter Lan-Shin Lee.

When combined with Gurihiru’s dynamic images of Superman standing up to racists in white hoods, Superman Smashes the Klan reminds us that the Man of Steel’s values might be old, but they’re needed all the more today.

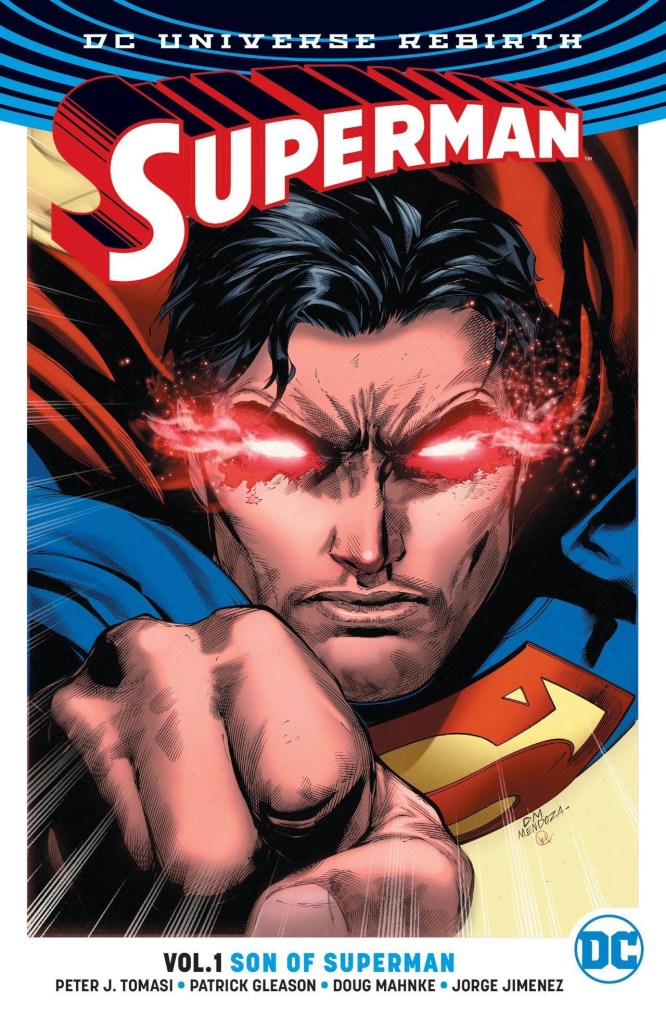

Superman: Rebirth (2016)

The Rebirth initiative sought to undo the status quo set by the New 52, DC Comics’ controversial company-wide reboot. Rebirth wasn’t another reboot, not exactly (it was explained away in-universe with a bunch of nonsense that involved Doctor Manhattan of Watchmen), but it did try to bring some characters back to their best versions, which posed quite a challenge for Superman. After all, he was dead.

Okay, the Superman of the New 52, a slightly underpowered and angrier version, had died after getting immense solar powers and using them to save the world. Around the same time cropped up a guy who looked a lot like him, a little bit older and with a beard, but otherwise very similar. And this guy had a wife named Lois and a kid named Jon. This was the pre-New 52 Superman, who somehow survived the Flashpoint reboot and had been lying low with his family ever since.

Is your head hurting? Well, don’t worry, because you don’t need to know too much of that nonsense to enjoy Superman: Rebirth. Instead, the series by writer Peter J. Tomasi and artists Jaime Mendoza and Doug Mahnke just plays like a straightforward Superman story, with a twist. This Superman has a super-son.

The excellent TV show Superman & Lois has taken some of the novelty off, but it’s impossible to understate how Rebirth revitalized Superman by taking away discussions about the Man of Steel being unrelatable because he’s so powerful. Instead, Superman becomes relatable because he’s a dad who makes the usual dad mistakes and has to balance love for his family with his responsibilities to the world.

Superman: Rebirth does what most reboots and relaunches often tried and failed, making Superman feel real and fantastic all at once.

The post The Comic Books That Defined Superman appeared first on Den of Geek.

0 Commentaires